My reading has slowed down this autumn. (Well, it’s winter now, and it still hasn’t sped back up.) I’m told this is understandable when one comes to the end of a large and demanding project, but it’s peculiarly frustrating. There are several shelves of books I want to read and talk about! Like Genevieve Cogman’s The Masked City and Becky Chambers’ The Long Way To A Small Angry Planet, and Jacey Bedford’s Winterwood, and Julia Knight’s Swords and Scoundrels, and Charlie Jane Anders’ All The Birds In The Sky. To say nothing of books published in years previous to this one…

But such is, as they say, life. This week I hope you’ll let me tell you about three interesting novels that I have managed to read recently.

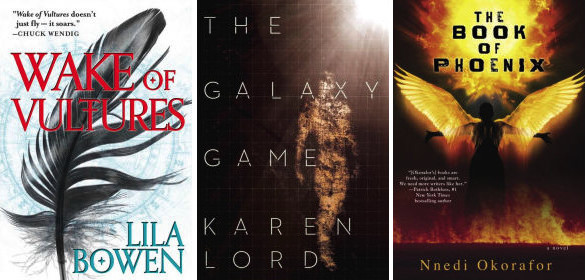

Lila Bowen’s Wake of Vultures is lately out from Orbit. (Bowen has also written as Delilah S. Dawson.) Set in a version of the early 19th-century American West with monsters and magic, Wake of Vultures stars Nettie Lonesome, aka Nat Lonesome, aka Rhett Hennessy: half-black, half-Indian, raised by white folks who didn’t call her a slave but treated her like one. When Nettie kills a man whose body dissolves into dust, she finds herself caught up in a peculiar destiny. One that involves killing monsters and learning who—and what—she is.

This is solid old-fashioned pulp adventure—with a non-binary-gendered non-white protagonist who’s attracted to both men and women. To me, that’s a number of points in its favour, even if I’m not normally a fan of US Western settings. And it’s fun.

I don’t know if I can describe Karen Lord’s The Galaxy Game (out last spring from Jo Fletcher Books) as “fun.” It’s interesting, and peculiar, and oddly gentle, though it sees revolutions and invasions take place. I cannot make sense of its structure: I do not understand why it makes the choice of viewpoints and viewpoint characters that it does. It seems more like a picaresque novel, a series of loosely connected incidents with no overarching plot. Science fiction as a genre is not usually given to the picaresque, and it’s a strange adjustment to make, as a reader: a jarring change to one’s assumptions about how narratives including spaceships and telepathy usually go. And yet the characters are sufficiently compelling that one finds oneself reading on, curious to see what next new change will come…

Nnedi Okorafor’s The Book of Phoenix is neither pulp nor picaresque. It is, instead, a complex, exciting book about personhood and power, colonisation and imperialism, villainy and truth. Phoenix is an accelerated organism, two years old but with the body and understanding of a forty-year-old woman. And other powers as well, powers the corporation that created her means to use as a weapon. But Phoenix is a woman with a will of her own, and when she achieves freedom from her creators, she’s going to make decisions that change the world—and maybe destroy it.

Like the rest of Okorafor’s science fiction (at least that I’ve read), The Book of Phoenix is willing to mingle the furniture of science fiction with the sensibilities of magical realism. The Book of Phoenix has a pointed political argument to make, the kind of argument about power and consequences science fiction has been making since its inception… but Okorafor opens up a universe that is wider and stranger and more interesting for its mythic and magical elements. The Book of Phoenix is fascinating and compelling, and I recommend it wholeheartedly.

What are you all reading?

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. She has recently completed a doctoral dissertation in Classics at Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter.